How To Lose 30 Pounds In 10 Days With Sensei's Island Diet

I recently went on a bike ride through downtown Cambridge and Boston with my friend Rob who is what you'd call an "urban forager." Rob knows his local trees better than anyone I know. As we stopped to take breaks along our route, Rob was constantly pointing out city trees that produced local nuts, berries, fruits, and even coffee substitutes. Some of these trees had been planted by "guerrilla foragers," meaning savvy individuals who had taken it upon themselves to plant these trees in the cities as a source of food.

I couldn't help but think of the news I had read that morning about the war in Ukraine.

In the news piece, they discussed how residents were forced to cut down local trees in the cities to make cooking fires, and their food supply had been cut off with only a few days remaining.

In the news piece, they discussed how residents were forced to cut down local trees in the cities to make cooking fires, and their food supply had been cut off with only a few days remaining.

It made me wonder— did they have local urban trees that they knew about that were sources of food?

Were there similar guerrilla foragers who had planted edible urban forests?

Were they forced to burn trees that supplied food?

I thought about how trees represent "survival" in some cultures, meaning that they can provide shelter, fire fuel, water (sap, rain-drip, and healthy groundwater), and food. It's no wonder that the proverbial Tree of Life is ubiquitous on many continents.

I also couldn't help but think about how here in North America, all major cities depend on transporting food from remote regions, and that major cities like New York and Los Angeles have only 4-7 days of food on the shelves to supply the population if transportation resources are cut off. This was a topic of a recent ninja blog.

I also couldn't help but think about how here in North America, all major cities depend on transporting food from remote regions, and that major cities like New York and Los Angeles have only 4-7 days of food on the shelves to supply the population if transportation resources are cut off. This was a topic of a recent ninja blog.

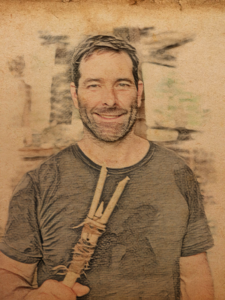

But on this cold winter bike ride with Rob, my mind also wandered to the warmer climes where many people this time of year venture to escape the cold. When I thought of both survival food and warm tropical islands, the first thing that came to mind was the story that Dai Shihan Mark Roemke told me about the food on his island survival trip.

So, I'll let Sensei Roemke tell you the tale first hand...

A couple years ago I went on an island survival trip with Tom McElroy. This was a group survival trip to the island of St. Croix. Before heading into the bush for our survival scenario, the instructors taught us local ways to make fire, how to identify edible plants, ways to make hunting tools, and how to construct a shelter using local materials. When we arrived at our location, the first thing that we did was focus on making our shelter because, if you have a shelter, you feel comfortable, which is key, especially with a group.

After we completed our preliminary training, we drove to a remote part of the island, then hiked several miles to our camp spot. Of the basic needs of survival: shelter, water, fire, and food, water was the one essential item that we brought with us to the site due to a lack of local fresh water. It became very apparent early on that you need calories to have energy to simply walk around, to travel to the beach to gather food, to gather almonds, to crack almond nuts and process the seeds, and to gather sea parsley. It was really important to carefully choose the actions you would do each day because your mind doesn't work as well when you are extremely hungry. For example, if you think that you are just going to go hunt after a few days without food, you quickly learn that it is much harder than you think just to perform the basic physical motions.

After we completed our preliminary training, we drove to a remote part of the island, then hiked several miles to our camp spot. Of the basic needs of survival: shelter, water, fire, and food, water was the one essential item that we brought with us to the site due to a lack of local fresh water. It became very apparent early on that you need calories to have energy to simply walk around, to travel to the beach to gather food, to gather almonds, to crack almond nuts and process the seeds, and to gather sea parsley. It was really important to carefully choose the actions you would do each day because your mind doesn't work as well when you are extremely hungry. For example, if you think that you are just going to go hunt after a few days without food, you quickly learn that it is much harder than you think just to perform the basic physical motions.

By the end of the ten day trip I had lost over 30 pounds. I learned that every day when you wake up, the primary thing that you think about is this— where am I going to get food?

This thinking takes over everything else. All other concerns pale in comparison to finding food. It is key to know your local edible foods. It's paramount to know what plants are poisonous. Above all, you need to learn when and where to gather wild edibles and how to process them.

*******

Back on my bike in Boston, I started thinking about sticks. When I lived in Hawaii, there was a local "pig dog" that was semi-feral that occasionally roamed the dirt road that crisscrossed the native forest on the way to my home outside of Volcano Village. When I rode my bike home, the hound often lay in wait and would chase me at full speed while snapping at my heels. As a kid I remembered my dad, who lived his whole life with one dog or another, telling me, "every dog knows what a stick means." By this, he meant that some were "fetchers" but other aggressive types knew that it wasn't a good idea to mess with someone wielding a big stick. He didn't mean that you should hit the animal, but instead, all you needed to do was to raise the stick above your head and the animal would back off.

With this in mind I picked up a large ohia tree branch as I biked home one day. Just like clockwork, as I rounded a corner by an old abandoned barn, here came the snarling pig dog. As he approached my heels I raised my large stick overhead and snarled back. What happened next was somewhat of a blur. In raising my stick quickly, I instantly disrupted my steering balance and went head-first over my handlebars. I remember watching the dog run away as the world turned upside down, followed by a crash into a nearby koa tree. I remember lying on my back, looking up at a slowly spinning front wheel. The dog's face looked down at me curiously, tail wagging. I threw the stick across the field and he ran off to fetch it. We were buddies after that day.

With this in mind I picked up a large ohia tree branch as I biked home one day. Just like clockwork, as I rounded a corner by an old abandoned barn, here came the snarling pig dog. As he approached my heels I raised my large stick overhead and snarled back. What happened next was somewhat of a blur. In raising my stick quickly, I instantly disrupted my steering balance and went head-first over my handlebars. I remember watching the dog run away as the world turned upside down, followed by a crash into a nearby koa tree. I remember lying on my back, looking up at a slowly spinning front wheel. The dog's face looked down at me curiously, tail wagging. I threw the stick across the field and he ran off to fetch it. We were buddies after that day.

As I hobbled home that day, I thought about sticks. I had just returned from a wilderness survival course in New Jersey. On the last day at that course, I asked the instructor, "what would be the first thing you'd do in a survival situation?" Without hesitation he looked me squarely and said...

"Get a stick!"

He went on to describe all the many uses of a stick in the wilderness— from making shelter, to tools, to fire, and especially for getting food.

Which brings me to today's training video. In the video below, Sensei Roemke demonstrates two ways of using a "throwing stick." This might be a scenario for self defense, or for getting food, such as knocking those island almonds out of a tree.

If you are someone who works with kids, check out our Ninja Mentor Lesson Plans. We have a specific plan that details how to teach the throwing stick skill below to youth.

In a billow of smoke, spindle squeals, and frustration, I quit. I was exhausted. I had burned eight holes already through my fire board, to no avail. I had busted blisters, bloody scraped knuckles, and rope burns. I was exhausted. I gave up. The instructor was right, time to go. As the cloud of smoke dissipated, I noticed something. There was a faint wisp that continued to drift quietly up from my tiny ash pile in the notch of my fire board! I blew gently on this. A red glow appeared from deep within the dark brown ashes. My first coal! I put it into my tinder bundle that had patiently awaited a coal for days. I gave a few blows and it erupted in flame. When this happened during the training week, people cheered and gave high fives. I was all alone in my celebration. I just sat down and smiled as I watched the small bundle burn down to ashes.

In a billow of smoke, spindle squeals, and frustration, I quit. I was exhausted. I had burned eight holes already through my fire board, to no avail. I had busted blisters, bloody scraped knuckles, and rope burns. I was exhausted. I gave up. The instructor was right, time to go. As the cloud of smoke dissipated, I noticed something. There was a faint wisp that continued to drift quietly up from my tiny ash pile in the notch of my fire board! I blew gently on this. A red glow appeared from deep within the dark brown ashes. My first coal! I put it into my tinder bundle that had patiently awaited a coal for days. I gave a few blows and it erupted in flame. When this happened during the training week, people cheered and gave high fives. I was all alone in my celebration. I just sat down and smiled as I watched the small bundle burn down to ashes. “Tonnie, got any tips?” I asked her. After the previous class of failing, or rather flailing to get a coal, I wanted an edge up on this next fire challenge. I had spent the entire year since my initial class, exploring the types of wood available in an island forest and practiced my bow drill skills intently every few days.

“Tonnie, got any tips?” I asked her. After the previous class of failing, or rather flailing to get a coal, I wanted an edge up on this next fire challenge. I had spent the entire year since my initial class, exploring the types of wood available in an island forest and practiced my bow drill skills intently every few days. A stone. Which directions should I go for a stone? I slowly turned a circle. As I rotated to the East, I felt pulled in this direction. I was a marathon runner at the time. I had jogged on the trails out from camp every morning. I was excited about this. I wanted to run. I took off immediately down the sandy trail heading out of camp.

A stone. Which directions should I go for a stone? I slowly turned a circle. As I rotated to the East, I felt pulled in this direction. I was a marathon runner at the time. I had jogged on the trails out from camp every morning. I was excited about this. I wanted to run. I took off immediately down the sandy trail heading out of camp. The sensation I experienced when I passed this trail reminded me of water skiing as a youth and being whipped around a corner as the boat turned and tugged on my rope. This little side trail tugged at me. Go this way, was the sensation, so I made a quick right turn. And there it was! A beautiful wedge shaped metamorphic stone in the middle of the trail. I grabbed it, and shifted into high gear for a sprint back to camp.

The sensation I experienced when I passed this trail reminded me of water skiing as a youth and being whipped around a corner as the boat turned and tugged on my rope. This little side trail tugged at me. Go this way, was the sensation, so I made a quick right turn. And there it was! A beautiful wedge shaped metamorphic stone in the middle of the trail. I grabbed it, and shifted into high gear for a sprint back to camp. Everyone slouched in silence. There were broken fragments of a stone on the ground which had crumbled in an attempt at making a notch with a soft stone in my absence. The fire board had a burned circle from the spindle with ash scattered around the burn mark. To get a coal with a bowdrill, you need a triangular notch carved in the board to catch the ash, which heats as it falls into the notch and turns to a coal. Without a proper notch, this attempt was doomed.

Everyone slouched in silence. There were broken fragments of a stone on the ground which had crumbled in an attempt at making a notch with a soft stone in my absence. The fire board had a burned circle from the spindle with ash scattered around the burn mark. To get a coal with a bowdrill, you need a triangular notch carved in the board to catch the ash, which heats as it falls into the notch and turns to a coal. Without a proper notch, this attempt was doomed. She started carving the notch again. It made the precise wedge cut needed into the center of the fire board. We now had all of the components assembled for the fire kit.

She started carving the notch again. It made the precise wedge cut needed into the center of the fire board. We now had all of the components assembled for the fire kit. Our fire-maker stopped bowing. There was a collective gasp from the crowd when they saw a small red coal in the notch of the fire board.

Our fire-maker stopped bowing. There was a collective gasp from the crowd when they saw a small red coal in the notch of the fire board.

So when you are looking out the spaceship window, less than .025% of what's down there can make it into your astronaut aqua-pack that is attached to the straw in your space helmet. Back on Earth, if you are lost in the wilderness, the deck is already stacked against you.

So when you are looking out the spaceship window, less than .025% of what's down there can make it into your astronaut aqua-pack that is attached to the straw in your space helmet. Back on Earth, if you are lost in the wilderness, the deck is already stacked against you. There's a couple ways to look at scenarios that could suddenly cut off our access to water. Survival skills courses often have one consider a situation of being "lost" in the wilderness, and needing to find fresh water to drink. While this happens to a relatively small handful of individuals annually, a more common experience that impacts many people, is that of a natural disaster suddenly shutting off the supply of fresh water. These types of disruptions are happening more frequently, and the topic of something we discussed in a

There's a couple ways to look at scenarios that could suddenly cut off our access to water. Survival skills courses often have one consider a situation of being "lost" in the wilderness, and needing to find fresh water to drink. While this happens to a relatively small handful of individuals annually, a more common experience that impacts many people, is that of a natural disaster suddenly shutting off the supply of fresh water. These types of disruptions are happening more frequently, and the topic of something we discussed in a  As I reached the bottom of this skylight, I found an entrance to the lava tube on either end of the large hole. The surprise that you often find just inside these entrances, are very unique bones. Before humans arrived on the islands, Hawaii was home to an array of flightless birds. Some, like rails, were relatively small, while others, such as a giant flightless duck, were over four feet tall. For some of these birds, they unfortunately would fall down into these large holes. Without the ability to fly out, they eventually died. Inside the entrances on either end I found piles of such bones. Some of these bones could be thousands of years old. Having spied some, I called for reinforcement.

As I reached the bottom of this skylight, I found an entrance to the lava tube on either end of the large hole. The surprise that you often find just inside these entrances, are very unique bones. Before humans arrived on the islands, Hawaii was home to an array of flightless birds. Some, like rails, were relatively small, while others, such as a giant flightless duck, were over four feet tall. For some of these birds, they unfortunately would fall down into these large holes. Without the ability to fly out, they eventually died. Inside the entrances on either end I found piles of such bones. Some of these bones could be thousands of years old. Having spied some, I called for reinforcement. "Those are probably old carbon fragments from an ancient Hawaiian torch. Someone was probably living in this lava tube. They were likely collecting water from the roots coming out of the ceiling up there. They would put gourds below the roots to catch water," one of them said, pointing to the ceiling of the lava tube where the roots of ohia and koa trees dangled down. Small drips of water were slowly dripping off the ends of the roots. I held my hand out and caught one on the tips of my fingers.

"Those are probably old carbon fragments from an ancient Hawaiian torch. Someone was probably living in this lava tube. They were likely collecting water from the roots coming out of the ceiling up there. They would put gourds below the roots to catch water," one of them said, pointing to the ceiling of the lava tube where the roots of ohia and koa trees dangled down. Small drips of water were slowly dripping off the ends of the roots. I held my hand out and caught one on the tips of my fingers. It involves a paper cup, or an empty glass bottle. Unfortunately (fortunately) there are plenty out there to be found in nature. I remember being mesmerized as a youth on a scout camping trip when first shown this technique. Still am. You can place a paper cup full of water on a bed of coals in a fire. The cup won't burn, and eventually the water will boil. Technically speaking, water needs to reach 158° F (70°C) for one minute to kill 99.999% of bacteria, protozoa, and viruses. Since water boils* at 212°F (100°C), this means that by the time water has reached the boiling point, it is safe to drink.

It involves a paper cup, or an empty glass bottle. Unfortunately (fortunately) there are plenty out there to be found in nature. I remember being mesmerized as a youth on a scout camping trip when first shown this technique. Still am. You can place a paper cup full of water on a bed of coals in a fire. The cup won't burn, and eventually the water will boil. Technically speaking, water needs to reach 158° F (70°C) for one minute to kill 99.999% of bacteria, protozoa, and viruses. Since water boils* at 212°F (100°C), this means that by the time water has reached the boiling point, it is safe to drink. Below is a short video showing one way to boil water with a paper cup on hot coals. You can do this also in a glass bottle, but here's a couple tips I learned the hard way...

Below is a short video showing one way to boil water with a paper cup on hot coals. You can do this also in a glass bottle, but here's a couple tips I learned the hard way...

Shelter is at the core of what gives us a sense of safety, security, confidence, and protection. It is central to the mindset of perseverance, which is one translation of the Japanese term "nin", as in ninja. Imagine if you will a disruptive scenario...

Shelter is at the core of what gives us a sense of safety, security, confidence, and protection. It is central to the mindset of perseverance, which is one translation of the Japanese term "nin", as in ninja. Imagine if you will a disruptive scenario... There's lots of debate though about what is the first thing you should approach. Typically the landscape dictates which should come first. For example, if the temperature is sub-zero with a windchill, you might need to focus on fire. If you were lost in a desert environment, you likely would want to focus on water as a top priority. We interviewed survival skills specialist

There's lots of debate though about what is the first thing you should approach. Typically the landscape dictates which should come first. For example, if the temperature is sub-zero with a windchill, you might need to focus on fire. If you were lost in a desert environment, you likely would want to focus on water as a top priority. We interviewed survival skills specialist  I remember learning this lesson many years ago when living in Hawaii. I was surfing at a river mouth north of Hilo on the Big Island. There had been a recent storm and lots of cold fresh water was rushing into the small bay where I waited for waves. Within a very short time my whole body was shaking and my fingernails were purple. I kept thinking, "How is this possible? I'm in Hawaii?!" When I tried to unlock my truck later, my hands were shaking so hard that I had a very difficult time getting the key in the slot. As I warmed up with the heater cranking in the front of the truck, I thought about how fast my body can lose heat, even in Hawaii.

I remember learning this lesson many years ago when living in Hawaii. I was surfing at a river mouth north of Hilo on the Big Island. There had been a recent storm and lots of cold fresh water was rushing into the small bay where I waited for waves. Within a very short time my whole body was shaking and my fingernails were purple. I kept thinking, "How is this possible? I'm in Hawaii?!" When I tried to unlock my truck later, my hands were shaking so hard that I had a very difficult time getting the key in the slot. As I warmed up with the heater cranking in the front of the truck, I thought about how fast my body can lose heat, even in Hawaii. I returned to Hawaii. The location where I opted to try this skill was a friend's property in a native koa forest at an elevation of 4500' on the side of Mauna Loa.It is a wet place. I mean, really wet. It gets over 150 inches of rain some years. I knew it would be a challenge to stay dry and warm (the temperature dipped into the 40's at night).

I returned to Hawaii. The location where I opted to try this skill was a friend's property in a native koa forest at an elevation of 4500' on the side of Mauna Loa.It is a wet place. I mean, really wet. It gets over 150 inches of rain some years. I knew it would be a challenge to stay dry and warm (the temperature dipped into the 40's at night). I returned to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey the following year, excited to build a debris shelter at the follow-up survival training course at the Tracker School. It was October and there were dry leaves everywhere! I worked on my shelter for 2-3 days in between lectures and other skills workshops. By time I was done, I had a giant mound of leaves and sticks about five feet high. I had made a door to keep the wind and rain out. I had even woven a reed mat as a sleeping pad. Thinking that the sound of the dawn chorus of birds would wake me, which usually happened in my tent, I went to sleep the first night without setting an alarm. My shelter was so soundproof that the next morning when I crawled out, I realized that I had not only missed breakfast, but the first lecture.

I returned to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey the following year, excited to build a debris shelter at the follow-up survival training course at the Tracker School. It was October and there were dry leaves everywhere! I worked on my shelter for 2-3 days in between lectures and other skills workshops. By time I was done, I had a giant mound of leaves and sticks about five feet high. I had made a door to keep the wind and rain out. I had even woven a reed mat as a sleeping pad. Thinking that the sound of the dawn chorus of birds would wake me, which usually happened in my tent, I went to sleep the first night without setting an alarm. My shelter was so soundproof that the next morning when I crawled out, I realized that I had not only missed breakfast, but the first lecture. Sleeping in that debris shelter changed the way I viewed my camping relation to the outdoors. I felt the confidence that I didn't need a sleeping bag or tent, and if needed, I could make a comfortable shelter with just the materials from the forest around me. But most important for me was the deep sense of connection and gratitude– the feeling that the Earth provided me everything I needed for shelter.

Sleeping in that debris shelter changed the way I viewed my camping relation to the outdoors. I felt the confidence that I didn't need a sleeping bag or tent, and if needed, I could make a comfortable shelter with just the materials from the forest around me. But most important for me was the deep sense of connection and gratitude– the feeling that the Earth provided me everything I needed for shelter. One of our favorite ways to introduce the basics of making a debris shelter is to create a "head shelter." This is a small scale version that incorporates all the essential components of a debris shelter: ridge pole, ribs, lattice, and debris. It's basically big enough to stick your head into.

One of our favorite ways to introduce the basics of making a debris shelter is to create a "head shelter." This is a small scale version that incorporates all the essential components of a debris shelter: ridge pole, ribs, lattice, and debris. It's basically big enough to stick your head into.

Brace yourself ninjas. I'm about to bum you out. But if you stick with me, there's rainbow unicorns at the end. I promise.

Brace yourself ninjas. I'm about to bum you out. But if you stick with me, there's rainbow unicorns at the end. I promise. Sui- the waters are rising in the ocean as the glaciers melt, and the rains fall with unseasonable force and frequency.

Sui- the waters are rising in the ocean as the glaciers melt, and the rains fall with unseasonable force and frequency. I've been closely following the climate science for decades, since my work in the wildlife conservation field began over thirty years ago. I worked with critically endangered birds in Hawaii for many years. Hawaii was and unfortunately still is considered "the endangered species capital of the United States." We are in the midst of what is now considered the

I've been closely following the climate science for decades, since my work in the wildlife conservation field began over thirty years ago. I worked with critically endangered birds in Hawaii for many years. Hawaii was and unfortunately still is considered "the endangered species capital of the United States." We are in the midst of what is now considered the  More recently, there is a new lexicon that has entered the climate change discussion from scientists, policy makers, and the public at large. These discussions include terms such as "tipping point," "the end of growth," "overreach," "collapsology," and even "the extinction of the human species." Many believe we have already passed the tipping point at which we can no longer hold back the devastation and disruption with increasing climate change. This discussion is supported by the fact that increasing average global temperature is no longer a linear progression with CO2 in the atmosphere. In other words, even if we could reverse, or remove the additional CO2 that began increasing with the industrial revolution, the climate would still continue to warm. This non-linear increase is due to things such as reduced solar reflection by snow in the polar regions, increased methane from melting permafrost in the arctic, subsurface oceanic methane release, and changes in the oceanic conveyor belt, to mention a few. There is a very real possibility that we have set things in motion that cannot be stopped at this point.

More recently, there is a new lexicon that has entered the climate change discussion from scientists, policy makers, and the public at large. These discussions include terms such as "tipping point," "the end of growth," "overreach," "collapsology," and even "the extinction of the human species." Many believe we have already passed the tipping point at which we can no longer hold back the devastation and disruption with increasing climate change. This discussion is supported by the fact that increasing average global temperature is no longer a linear progression with CO2 in the atmosphere. In other words, even if we could reverse, or remove the additional CO2 that began increasing with the industrial revolution, the climate would still continue to warm. This non-linear increase is due to things such as reduced solar reflection by snow in the polar regions, increased methane from melting permafrost in the arctic, subsurface oceanic methane release, and changes in the oceanic conveyor belt, to mention a few. There is a very real possibility that we have set things in motion that cannot be stopped at this point. We are also on course for the end of growth, meaning when the growth of civilization collides with the end of finite resources, in other words the "collapse of civilization." This is predicted to occur

We are also on course for the end of growth, meaning when the growth of civilization collides with the end of finite resources, in other words the "collapse of civilization." This is predicted to occur  A 2018 article

A 2018 article  How prepared are we currently for an economic and ecological societal collapse? More than 95% of the food coming into the major cities in our country arrives by long-distance trucking. If this ceased, it is estimated that New York would have a four day supply of food. Los Angeles would have three days of food. In 1880, 50% of Americans were farmers. Today, that number is less than 2%. In 1945, Americans grew 40% of their food in backyard gardens. That number is now less than 0.1%. This is homeland insecurity. I wonder how many Americans today can identify a single wild edible plant? How many know the ubiquitous edible "weeds" in their yards, that they kill with glyphosate herbicides at the cost to their own fertility and health? As I look out my kitchen window during the winter, I ask myself— how can I expand and grow more? What new wild edibles can I learn and find in the nearby forests?

How prepared are we currently for an economic and ecological societal collapse? More than 95% of the food coming into the major cities in our country arrives by long-distance trucking. If this ceased, it is estimated that New York would have a four day supply of food. Los Angeles would have three days of food. In 1880, 50% of Americans were farmers. Today, that number is less than 2%. In 1945, Americans grew 40% of their food in backyard gardens. That number is now less than 0.1%. This is homeland insecurity. I wonder how many Americans today can identify a single wild edible plant? How many know the ubiquitous edible "weeds" in their yards, that they kill with glyphosate herbicides at the cost to their own fertility and health? As I look out my kitchen window during the winter, I ask myself— how can I expand and grow more? What new wild edibles can I learn and find in the nearby forests? These realizations, however, have given me an awakened perspective on the value and role of the art of the ninja when faced with the possibility of collapse. If you examine historical examples of societal collapse, wars or social unrest typically precede or follow the downfall of civilizations. While actually having to defend yourself or others when faced with unrest might be a real matter worthy of discussion, there is a deeper value that I find in the art. The essence of perseverance, or the meaning of "nin," is at the heart of what motivates me daily when I wake. What am I going to do today, to take a necessary step towards adapting to the unknown that lies on the horizon? I have been teaching survival skills for years. Beyond shelter, water, fire, and food, we teach that attitude is the most important survival skill. If you give up, and admit defeat in the face of doom, then you most likely will fail. Remembering to embody the spirit of "nin" is thus essential to survival.

These realizations, however, have given me an awakened perspective on the value and role of the art of the ninja when faced with the possibility of collapse. If you examine historical examples of societal collapse, wars or social unrest typically precede or follow the downfall of civilizations. While actually having to defend yourself or others when faced with unrest might be a real matter worthy of discussion, there is a deeper value that I find in the art. The essence of perseverance, or the meaning of "nin," is at the heart of what motivates me daily when I wake. What am I going to do today, to take a necessary step towards adapting to the unknown that lies on the horizon? I have been teaching survival skills for years. Beyond shelter, water, fire, and food, we teach that attitude is the most important survival skill. If you give up, and admit defeat in the face of doom, then you most likely will fail. Remembering to embody the spirit of "nin" is thus essential to survival. I posed this question to Dai Shihan Mark Roemke regarding this topic: How does the art of the ninja relate to an uncertain future of disruption on our planet? Here is his response.

I posed this question to Dai Shihan Mark Roemke regarding this topic: How does the art of the ninja relate to an uncertain future of disruption on our planet? Here is his response. Beyond my garden, I think about my own kids and the youth I have encountered with the programs I teach. I realize that to simply hope that our governments and corporations can figure out a solution to climate change while continuing "business as usual" is not only foolish, but does an extreme disservice to the youth of today and the future generations. If I make it to 2045, I'll be firmly in my elder years. My kids, grandkids, or great grandkids (if there are still enough viable sperm and eggs by then) will be the ones facing the brunt of this trajectory. There's a song that I love that has the words that speak to this:

Beyond my garden, I think about my own kids and the youth I have encountered with the programs I teach. I realize that to simply hope that our governments and corporations can figure out a solution to climate change while continuing "business as usual" is not only foolish, but does an extreme disservice to the youth of today and the future generations. If I make it to 2045, I'll be firmly in my elder years. My kids, grandkids, or great grandkids (if there are still enough viable sperm and eggs by then) will be the ones facing the brunt of this trajectory. There's a song that I love that has the words that speak to this: I also have a new perspective on the large volume of skills that we have put together for youth with our Ninjas in Nature program. I used to view them primarily as a means to help someone connect deeply to nature, while building powerful self sufficiency, awareness, and self confidence through the martial arts skills. Connect someone deeply to nature, and they will want to save it was once the standard mantra. The end result was a truly happy and whole being, with a desire to preserve nature, and still is. Unfortunately, the pragmatist and former Boys Scout in me remembers the old motto: "be prepared." How to prepare for an uncertain future, with no template from history to go by, is at the core of this challenge for me.

I also have a new perspective on the large volume of skills that we have put together for youth with our Ninjas in Nature program. I used to view them primarily as a means to help someone connect deeply to nature, while building powerful self sufficiency, awareness, and self confidence through the martial arts skills. Connect someone deeply to nature, and they will want to save it was once the standard mantra. The end result was a truly happy and whole being, with a desire to preserve nature, and still is. Unfortunately, the pragmatist and former Boys Scout in me remembers the old motto: "be prepared." How to prepare for an uncertain future, with no template from history to go by, is at the core of this challenge for me. But now I see these skills as essential tools for adapting to the unknown change and disruptions to be faced by the inhabitants of our planet. It's not just the confidence of knowing how to find and process acorns as a vital protein source should the shipping trucks cease to show up, or how to make a fire by friction if the electricity goes down. It's about how to tap into the spirit of perseverance.

But now I see these skills as essential tools for adapting to the unknown change and disruptions to be faced by the inhabitants of our planet. It's not just the confidence of knowing how to find and process acorns as a vital protein source should the shipping trucks cease to show up, or how to make a fire by friction if the electricity goes down. It's about how to tap into the spirit of perseverance. Over 98% of all life that has ever lived on this planet has gone extinct. Think about that. The deck was stacked against us as a species long before we ever appeared on this planet. There have been five major extinction events in the history of planet Earth, and we likely are driving the current extinction bus blindly towards the precipice of the sixth. Still, after every major extinction event, something more beautiful evolved in the aftermath. Dinosaurs and ferns were pretty cool, but the mammals and flowering plants that followed were much more beautiful. I know. I'm a biased mammal. Still, I think the photographers and landscape artists are on my side. While this may sound like a nihilistic doomsday perspective, I find solace in stepping back to look at the wide angle vision, long view of our human time on Earth, and our collective connection to the mystery that holds this tapestry together. There is a beauty to this mystery that we are part of. One definition that I heard recently for "love" is a state of consciousness that is an awareness of beauty. I love the mystery.

Over 98% of all life that has ever lived on this planet has gone extinct. Think about that. The deck was stacked against us as a species long before we ever appeared on this planet. There have been five major extinction events in the history of planet Earth, and we likely are driving the current extinction bus blindly towards the precipice of the sixth. Still, after every major extinction event, something more beautiful evolved in the aftermath. Dinosaurs and ferns were pretty cool, but the mammals and flowering plants that followed were much more beautiful. I know. I'm a biased mammal. Still, I think the photographers and landscape artists are on my side. While this may sound like a nihilistic doomsday perspective, I find solace in stepping back to look at the wide angle vision, long view of our human time on Earth, and our collective connection to the mystery that holds this tapestry together. There is a beauty to this mystery that we are part of. One definition that I heard recently for "love" is a state of consciousness that is an awareness of beauty. I love the mystery.

By Dai Shihan Mark Roemke

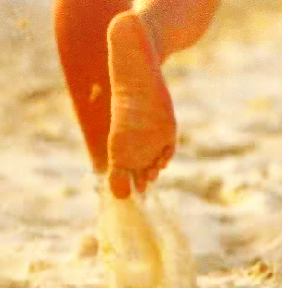

By Dai Shihan Mark Roemke As students progress over the years through the martial arts, you can see them drop from being in their head, down into their shoulders, their waist, their knees, and eventually the ankles and feet. When this happens, you have a complete being who is very solid in their own stature, feeling, and energy. We call this person a grounded martial artist.

As students progress over the years through the martial arts, you can see them drop from being in their head, down into their shoulders, their waist, their knees, and eventually the ankles and feet. When this happens, you have a complete being who is very solid in their own stature, feeling, and energy. We call this person a grounded martial artist. The physical part of grounding leads to the mind, which leads to the spirit. The way to tap into this is called “Earthing.” This involves taking off your shoes and sinking your feet into the ground beneath you. I recommend hiking in nature without your shoes on. This can be a little challenging at first if your feet are tender, but you can find a grassy field to try to experience this feeling.

The physical part of grounding leads to the mind, which leads to the spirit. The way to tap into this is called “Earthing.” This involves taking off your shoes and sinking your feet into the ground beneath you. I recommend hiking in nature without your shoes on. This can be a little challenging at first if your feet are tender, but you can find a grassy field to try to experience this feeling.

In our

In our  Megumi Whittle describes herself with one word— passion. Her personal mission is to "...share the joy that empowers us to become better selves."

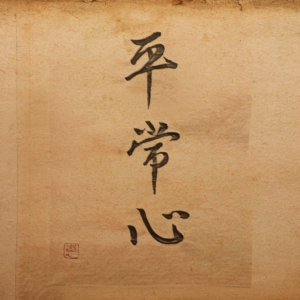

Megumi Whittle describes herself with one word— passion. Her personal mission is to "...share the joy that empowers us to become better selves." Megumi: I think that both are essential— they go side by side, and they are parts of a whole. There is an idiom called 文武両道 (Bunbu Ryōdō). Hatsumi Sensei mentions this in one of his books. He says, “...to follow both roads of scholarship and war. Do not become too absorbed by only one of them.” This idiom is widely used in many schools and dojos as a motto to commit to both scholarship and sports/martial arts. Also, it is used as a phrase that means to be good at both literature and sports. Historically, both 文 and 武 were the expected expertise for leaders. 文 may include calligraphy, arts, tea, poems etc. Having both qualities were equally valued.

Megumi: I think that both are essential— they go side by side, and they are parts of a whole. There is an idiom called 文武両道 (Bunbu Ryōdō). Hatsumi Sensei mentions this in one of his books. He says, “...to follow both roads of scholarship and war. Do not become too absorbed by only one of them.” This idiom is widely used in many schools and dojos as a motto to commit to both scholarship and sports/martial arts. Also, it is used as a phrase that means to be good at both literature and sports. Historically, both 文 and 武 were the expected expertise for leaders. 文 may include calligraphy, arts, tea, poems etc. Having both qualities were equally valued. Megumi: Many come to my mind. If I have to choose one, it would be 心 技 体.

Megumi: Many come to my mind. If I have to choose one, it would be 心 技 体. Pathways: For someone new to the art of calligraphy, what do you recommend for a starting point for training in this art?

Pathways: For someone new to the art of calligraphy, what do you recommend for a starting point for training in this art?

There are so many amazing things about watching Soke wield a brush as the Grandmaster, as a martial artist, and as an artist. His art is an extension of who he is. His books and the walls of the Hombu dojo are filled with his paintings. His art also hangs on the walls of my home and in every one of my dojos.

There are so many amazing things about watching Soke wield a brush as the Grandmaster, as a martial artist, and as an artist. His art is an extension of who he is. His books and the walls of the Hombu dojo are filled with his paintings. His art also hangs on the walls of my home and in every one of my dojos.

In the early 1980's, a national health crisis emerged in Japan that resulted from increasing industrialization and a culture of overwork. During this time, researchers in Japan discovered that trees released certain chemicals to protect themselves and the forest around them from diseases and pests. They discovered when humans were exposed to these chemicals known as phytoncides, they too demonstrated increased health and vigor as evidenced by elevated moods, lowered stress hormones, increased immune responses and more. Government officials in Japan encouraged people to practice “Shinrin-yoku” which translates to “bathe in the forest atmosphere” and thus “Forest Bathing” was born.

In the early 1980's, a national health crisis emerged in Japan that resulted from increasing industrialization and a culture of overwork. During this time, researchers in Japan discovered that trees released certain chemicals to protect themselves and the forest around them from diseases and pests. They discovered when humans were exposed to these chemicals known as phytoncides, they too demonstrated increased health and vigor as evidenced by elevated moods, lowered stress hormones, increased immune responses and more. Government officials in Japan encouraged people to practice “Shinrin-yoku” which translates to “bathe in the forest atmosphere” and thus “Forest Bathing” was born. Pathways: For people not familiar with Forest Therapy or the Japanese practice of Shinrin-yoku, could you describe this practice?

Pathways: For people not familiar with Forest Therapy or the Japanese practice of Shinrin-yoku, could you describe this practice? Caitlin: There are so many benefits to forest bathing and simply spending time in nature. There is a growing body of scientific research that confirms what seems like an obvious truth— human beings benefit from engaging with the natural world. The list of well documented benefits of forest bathing is quite extensive. Benefits include lowered cortisol and stress hormones, reduced inflammation, elevated mood, lowered blood pressure, increased focus and attention, and enhanced creativity. There are many more documented benefits. One of the most exciting discoveries, which sparked the movement of Forest Bathing, is the discovery that chemicals released by trees to protect themselves and their forest communities from pests and diseases also dramatically enhance immunity in human beings. When we spend time in nature, and specifically amongst trees, we are exposed to these chemicals and it causes our immune systems to produce a special white blood cell called a "natural killer cell". It's a scary little name for a highly beneficial cell that has the ability to find and combat disease in a cell before the cell has any signs of damage. In a sense, the forest has the potential to heal us before we are even sick.

Caitlin: There are so many benefits to forest bathing and simply spending time in nature. There is a growing body of scientific research that confirms what seems like an obvious truth— human beings benefit from engaging with the natural world. The list of well documented benefits of forest bathing is quite extensive. Benefits include lowered cortisol and stress hormones, reduced inflammation, elevated mood, lowered blood pressure, increased focus and attention, and enhanced creativity. There are many more documented benefits. One of the most exciting discoveries, which sparked the movement of Forest Bathing, is the discovery that chemicals released by trees to protect themselves and their forest communities from pests and diseases also dramatically enhance immunity in human beings. When we spend time in nature, and specifically amongst trees, we are exposed to these chemicals and it causes our immune systems to produce a special white blood cell called a "natural killer cell". It's a scary little name for a highly beneficial cell that has the ability to find and combat disease in a cell before the cell has any signs of damage. In a sense, the forest has the potential to heal us before we are even sick. There are two outcomes that are most universal and profound for people. One is the increased understanding of how to create a non-coercive experience for others. Learning to do this is a big part of the training and it is also profound because it is something that is rarely modeled or experienced in the western world. The other outcome that is closely tied with this is an increased faith in nature to give people exactly what they need, when they need it.

There are two outcomes that are most universal and profound for people. One is the increased understanding of how to create a non-coercive experience for others. Learning to do this is a big part of the training and it is also profound because it is something that is rarely modeled or experienced in the western world. The other outcome that is closely tied with this is an increased faith in nature to give people exactly what they need, when they need it. Caitlin: I think one of the coveted gifts of this martial art is the ability to blend in and to be invisible. Besides the obvious health benefits that I already mentioned, I think this practice may be of particular interest to a ninjutsu practitioner for one simple and esoteric reason—you do not become invisible by hiding in the forest. You become invisible by being hidden by the forest. It takes attunement and relationship-building with nature to understand how to let the land fold you into itself. Attunement with nature is at the heart of the forest therapy guide training.

Caitlin: I think one of the coveted gifts of this martial art is the ability to blend in and to be invisible. Besides the obvious health benefits that I already mentioned, I think this practice may be of particular interest to a ninjutsu practitioner for one simple and esoteric reason—you do not become invisible by hiding in the forest. You become invisible by being hidden by the forest. It takes attunement and relationship-building with nature to understand how to let the land fold you into itself. Attunement with nature is at the heart of the forest therapy guide training. There is a little book I love called "What a Plant Knows" by Daniel Chamovitz. It's all about the sensory experience of plants that science has confirmed thus far. The first sentence of the book says "Think about this: plants see you." I think it is important to take this type of understanding with us into our forest bathing experiences because not only does it increase the benefits that we as humans get from the experience, but it also increases the likelihood that we will develop a sense of stewardship and reciprocity with the natural world. It matters that we understand we are not alone in this world, for our own health, and for the health of this world we co-occupy with other life.

There is a little book I love called "What a Plant Knows" by Daniel Chamovitz. It's all about the sensory experience of plants that science has confirmed thus far. The first sentence of the book says "Think about this: plants see you." I think it is important to take this type of understanding with us into our forest bathing experiences because not only does it increase the benefits that we as humans get from the experience, but it also increases the likelihood that we will develop a sense of stewardship and reciprocity with the natural world. It matters that we understand we are not alone in this world, for our own health, and for the health of this world we co-occupy with other life.