How To Lose 30 Pounds In 10 Days With Sensei's Island Diet

I recently went on a bike ride through downtown Cambridge and Boston with my friend Rob who is what you'd call an "urban forager." Rob knows his local trees better than anyone I know. As we stopped to take breaks along our route, Rob was constantly pointing out city trees that produced local nuts, berries, fruits, and even coffee substitutes. Some of these trees had been planted by "guerrilla foragers," meaning savvy individuals who had taken it upon themselves to plant these trees in the cities as a source of food.

I couldn't help but think of the news I had read that morning about the war in Ukraine.

In the news piece, they discussed how residents were forced to cut down local trees in the cities to make cooking fires, and their food supply had been cut off with only a few days remaining.

In the news piece, they discussed how residents were forced to cut down local trees in the cities to make cooking fires, and their food supply had been cut off with only a few days remaining.

It made me wonder— did they have local urban trees that they knew about that were sources of food?

Were there similar guerrilla foragers who had planted edible urban forests?

Were they forced to burn trees that supplied food?

I thought about how trees represent "survival" in some cultures, meaning that they can provide shelter, fire fuel, water (sap, rain-drip, and healthy groundwater), and food. It's no wonder that the proverbial Tree of Life is ubiquitous on many continents.

I also couldn't help but think about how here in North America, all major cities depend on transporting food from remote regions, and that major cities like New York and Los Angeles have only 4-7 days of food on the shelves to supply the population if transportation resources are cut off. This was a topic of a recent ninja blog.

I also couldn't help but think about how here in North America, all major cities depend on transporting food from remote regions, and that major cities like New York and Los Angeles have only 4-7 days of food on the shelves to supply the population if transportation resources are cut off. This was a topic of a recent ninja blog.

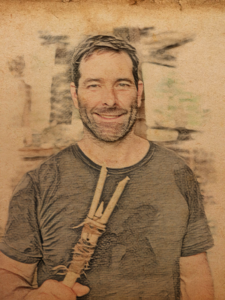

But on this cold winter bike ride with Rob, my mind also wandered to the warmer climes where many people this time of year venture to escape the cold. When I thought of both survival food and warm tropical islands, the first thing that came to mind was the story that Dai Shihan Mark Roemke told me about the food on his island survival trip.

So, I'll let Sensei Roemke tell you the tale first hand...

A couple years ago I went on an island survival trip with Tom McElroy. This was a group survival trip to the island of St. Croix. Before heading into the bush for our survival scenario, the instructors taught us local ways to make fire, how to identify edible plants, ways to make hunting tools, and how to construct a shelter using local materials. When we arrived at our location, the first thing that we did was focus on making our shelter because, if you have a shelter, you feel comfortable, which is key, especially with a group.

After we completed our preliminary training, we drove to a remote part of the island, then hiked several miles to our camp spot. Of the basic needs of survival: shelter, water, fire, and food, water was the one essential item that we brought with us to the site due to a lack of local fresh water. It became very apparent early on that you need calories to have energy to simply walk around, to travel to the beach to gather food, to gather almonds, to crack almond nuts and process the seeds, and to gather sea parsley. It was really important to carefully choose the actions you would do each day because your mind doesn't work as well when you are extremely hungry. For example, if you think that you are just going to go hunt after a few days without food, you quickly learn that it is much harder than you think just to perform the basic physical motions.

After we completed our preliminary training, we drove to a remote part of the island, then hiked several miles to our camp spot. Of the basic needs of survival: shelter, water, fire, and food, water was the one essential item that we brought with us to the site due to a lack of local fresh water. It became very apparent early on that you need calories to have energy to simply walk around, to travel to the beach to gather food, to gather almonds, to crack almond nuts and process the seeds, and to gather sea parsley. It was really important to carefully choose the actions you would do each day because your mind doesn't work as well when you are extremely hungry. For example, if you think that you are just going to go hunt after a few days without food, you quickly learn that it is much harder than you think just to perform the basic physical motions.

By the end of the ten day trip I had lost over 30 pounds. I learned that every day when you wake up, the primary thing that you think about is this— where am I going to get food?

This thinking takes over everything else. All other concerns pale in comparison to finding food. It is key to know your local edible foods. It's paramount to know what plants are poisonous. Above all, you need to learn when and where to gather wild edibles and how to process them.

*******

Back on my bike in Boston, I started thinking about sticks. When I lived in Hawaii, there was a local "pig dog" that was semi-feral that occasionally roamed the dirt road that crisscrossed the native forest on the way to my home outside of Volcano Village. When I rode my bike home, the hound often lay in wait and would chase me at full speed while snapping at my heels. As a kid I remembered my dad, who lived his whole life with one dog or another, telling me, "every dog knows what a stick means." By this, he meant that some were "fetchers" but other aggressive types knew that it wasn't a good idea to mess with someone wielding a big stick. He didn't mean that you should hit the animal, but instead, all you needed to do was to raise the stick above your head and the animal would back off.

With this in mind I picked up a large ohia tree branch as I biked home one day. Just like clockwork, as I rounded a corner by an old abandoned barn, here came the snarling pig dog. As he approached my heels I raised my large stick overhead and snarled back. What happened next was somewhat of a blur. In raising my stick quickly, I instantly disrupted my steering balance and went head-first over my handlebars. I remember watching the dog run away as the world turned upside down, followed by a crash into a nearby koa tree. I remember lying on my back, looking up at a slowly spinning front wheel. The dog's face looked down at me curiously, tail wagging. I threw the stick across the field and he ran off to fetch it. We were buddies after that day.

With this in mind I picked up a large ohia tree branch as I biked home one day. Just like clockwork, as I rounded a corner by an old abandoned barn, here came the snarling pig dog. As he approached my heels I raised my large stick overhead and snarled back. What happened next was somewhat of a blur. In raising my stick quickly, I instantly disrupted my steering balance and went head-first over my handlebars. I remember watching the dog run away as the world turned upside down, followed by a crash into a nearby koa tree. I remember lying on my back, looking up at a slowly spinning front wheel. The dog's face looked down at me curiously, tail wagging. I threw the stick across the field and he ran off to fetch it. We were buddies after that day.

As I hobbled home that day, I thought about sticks. I had just returned from a wilderness survival course in New Jersey. On the last day at that course, I asked the instructor, "what would be the first thing you'd do in a survival situation?" Without hesitation he looked me squarely and said...

"Get a stick!"

He went on to describe all the many uses of a stick in the wilderness— from making shelter, to tools, to fire, and especially for getting food.

Which brings me to today's training video. In the video below, Sensei Roemke demonstrates two ways of using a "throwing stick." This might be a scenario for self defense, or for getting food, such as knocking those island almonds out of a tree.

If you are someone who works with kids, check out our Ninja Mentor Lesson Plans. We have a specific plan that details how to teach the throwing stick skill below to youth.

In a billow of smoke, spindle squeals, and frustration, I quit. I was exhausted. I had burned eight holes already through my fire board, to no avail. I had busted blisters, bloody scraped knuckles, and rope burns. I was exhausted. I gave up. The instructor was right, time to go. As the cloud of smoke dissipated, I noticed something. There was a faint wisp that continued to drift quietly up from my tiny ash pile in the notch of my fire board! I blew gently on this. A red glow appeared from deep within the dark brown ashes. My first coal! I put it into my tinder bundle that had patiently awaited a coal for days. I gave a few blows and it erupted in flame. When this happened during the training week, people cheered and gave high fives. I was all alone in my celebration. I just sat down and smiled as I watched the small bundle burn down to ashes.

In a billow of smoke, spindle squeals, and frustration, I quit. I was exhausted. I had burned eight holes already through my fire board, to no avail. I had busted blisters, bloody scraped knuckles, and rope burns. I was exhausted. I gave up. The instructor was right, time to go. As the cloud of smoke dissipated, I noticed something. There was a faint wisp that continued to drift quietly up from my tiny ash pile in the notch of my fire board! I blew gently on this. A red glow appeared from deep within the dark brown ashes. My first coal! I put it into my tinder bundle that had patiently awaited a coal for days. I gave a few blows and it erupted in flame. When this happened during the training week, people cheered and gave high fives. I was all alone in my celebration. I just sat down and smiled as I watched the small bundle burn down to ashes. “Tonnie, got any tips?” I asked her. After the previous class of failing, or rather flailing to get a coal, I wanted an edge up on this next fire challenge. I had spent the entire year since my initial class, exploring the types of wood available in an island forest and practiced my bow drill skills intently every few days.

“Tonnie, got any tips?” I asked her. After the previous class of failing, or rather flailing to get a coal, I wanted an edge up on this next fire challenge. I had spent the entire year since my initial class, exploring the types of wood available in an island forest and practiced my bow drill skills intently every few days. A stone. Which directions should I go for a stone? I slowly turned a circle. As I rotated to the East, I felt pulled in this direction. I was a marathon runner at the time. I had jogged on the trails out from camp every morning. I was excited about this. I wanted to run. I took off immediately down the sandy trail heading out of camp.

A stone. Which directions should I go for a stone? I slowly turned a circle. As I rotated to the East, I felt pulled in this direction. I was a marathon runner at the time. I had jogged on the trails out from camp every morning. I was excited about this. I wanted to run. I took off immediately down the sandy trail heading out of camp. The sensation I experienced when I passed this trail reminded me of water skiing as a youth and being whipped around a corner as the boat turned and tugged on my rope. This little side trail tugged at me. Go this way, was the sensation, so I made a quick right turn. And there it was! A beautiful wedge shaped metamorphic stone in the middle of the trail. I grabbed it, and shifted into high gear for a sprint back to camp.

The sensation I experienced when I passed this trail reminded me of water skiing as a youth and being whipped around a corner as the boat turned and tugged on my rope. This little side trail tugged at me. Go this way, was the sensation, so I made a quick right turn. And there it was! A beautiful wedge shaped metamorphic stone in the middle of the trail. I grabbed it, and shifted into high gear for a sprint back to camp. Everyone slouched in silence. There were broken fragments of a stone on the ground which had crumbled in an attempt at making a notch with a soft stone in my absence. The fire board had a burned circle from the spindle with ash scattered around the burn mark. To get a coal with a bowdrill, you need a triangular notch carved in the board to catch the ash, which heats as it falls into the notch and turns to a coal. Without a proper notch, this attempt was doomed.

Everyone slouched in silence. There were broken fragments of a stone on the ground which had crumbled in an attempt at making a notch with a soft stone in my absence. The fire board had a burned circle from the spindle with ash scattered around the burn mark. To get a coal with a bowdrill, you need a triangular notch carved in the board to catch the ash, which heats as it falls into the notch and turns to a coal. Without a proper notch, this attempt was doomed. She started carving the notch again. It made the precise wedge cut needed into the center of the fire board. We now had all of the components assembled for the fire kit.

She started carving the notch again. It made the precise wedge cut needed into the center of the fire board. We now had all of the components assembled for the fire kit. Our fire-maker stopped bowing. There was a collective gasp from the crowd when they saw a small red coal in the notch of the fire board.

Our fire-maker stopped bowing. There was a collective gasp from the crowd when they saw a small red coal in the notch of the fire board.

Shelter is at the core of what gives us a sense of safety, security, confidence, and protection. It is central to the mindset of perseverance, which is one translation of the Japanese term "nin", as in ninja. Imagine if you will a disruptive scenario...

Shelter is at the core of what gives us a sense of safety, security, confidence, and protection. It is central to the mindset of perseverance, which is one translation of the Japanese term "nin", as in ninja. Imagine if you will a disruptive scenario... There's lots of debate though about what is the first thing you should approach. Typically the landscape dictates which should come first. For example, if the temperature is sub-zero with a windchill, you might need to focus on fire. If you were lost in a desert environment, you likely would want to focus on water as a top priority. We interviewed survival skills specialist

There's lots of debate though about what is the first thing you should approach. Typically the landscape dictates which should come first. For example, if the temperature is sub-zero with a windchill, you might need to focus on fire. If you were lost in a desert environment, you likely would want to focus on water as a top priority. We interviewed survival skills specialist  I remember learning this lesson many years ago when living in Hawaii. I was surfing at a river mouth north of Hilo on the Big Island. There had been a recent storm and lots of cold fresh water was rushing into the small bay where I waited for waves. Within a very short time my whole body was shaking and my fingernails were purple. I kept thinking, "How is this possible? I'm in Hawaii?!" When I tried to unlock my truck later, my hands were shaking so hard that I had a very difficult time getting the key in the slot. As I warmed up with the heater cranking in the front of the truck, I thought about how fast my body can lose heat, even in Hawaii.

I remember learning this lesson many years ago when living in Hawaii. I was surfing at a river mouth north of Hilo on the Big Island. There had been a recent storm and lots of cold fresh water was rushing into the small bay where I waited for waves. Within a very short time my whole body was shaking and my fingernails were purple. I kept thinking, "How is this possible? I'm in Hawaii?!" When I tried to unlock my truck later, my hands were shaking so hard that I had a very difficult time getting the key in the slot. As I warmed up with the heater cranking in the front of the truck, I thought about how fast my body can lose heat, even in Hawaii. I returned to Hawaii. The location where I opted to try this skill was a friend's property in a native koa forest at an elevation of 4500' on the side of Mauna Loa.It is a wet place. I mean, really wet. It gets over 150 inches of rain some years. I knew it would be a challenge to stay dry and warm (the temperature dipped into the 40's at night).

I returned to Hawaii. The location where I opted to try this skill was a friend's property in a native koa forest at an elevation of 4500' on the side of Mauna Loa.It is a wet place. I mean, really wet. It gets over 150 inches of rain some years. I knew it would be a challenge to stay dry and warm (the temperature dipped into the 40's at night). I returned to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey the following year, excited to build a debris shelter at the follow-up survival training course at the Tracker School. It was October and there were dry leaves everywhere! I worked on my shelter for 2-3 days in between lectures and other skills workshops. By time I was done, I had a giant mound of leaves and sticks about five feet high. I had made a door to keep the wind and rain out. I had even woven a reed mat as a sleeping pad. Thinking that the sound of the dawn chorus of birds would wake me, which usually happened in my tent, I went to sleep the first night without setting an alarm. My shelter was so soundproof that the next morning when I crawled out, I realized that I had not only missed breakfast, but the first lecture.

I returned to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey the following year, excited to build a debris shelter at the follow-up survival training course at the Tracker School. It was October and there were dry leaves everywhere! I worked on my shelter for 2-3 days in between lectures and other skills workshops. By time I was done, I had a giant mound of leaves and sticks about five feet high. I had made a door to keep the wind and rain out. I had even woven a reed mat as a sleeping pad. Thinking that the sound of the dawn chorus of birds would wake me, which usually happened in my tent, I went to sleep the first night without setting an alarm. My shelter was so soundproof that the next morning when I crawled out, I realized that I had not only missed breakfast, but the first lecture. Sleeping in that debris shelter changed the way I viewed my camping relation to the outdoors. I felt the confidence that I didn't need a sleeping bag or tent, and if needed, I could make a comfortable shelter with just the materials from the forest around me. But most important for me was the deep sense of connection and gratitude– the feeling that the Earth provided me everything I needed for shelter.

Sleeping in that debris shelter changed the way I viewed my camping relation to the outdoors. I felt the confidence that I didn't need a sleeping bag or tent, and if needed, I could make a comfortable shelter with just the materials from the forest around me. But most important for me was the deep sense of connection and gratitude– the feeling that the Earth provided me everything I needed for shelter. One of our favorite ways to introduce the basics of making a debris shelter is to create a "head shelter." This is a small scale version that incorporates all the essential components of a debris shelter: ridge pole, ribs, lattice, and debris. It's basically big enough to stick your head into.

One of our favorite ways to introduce the basics of making a debris shelter is to create a "head shelter." This is a small scale version that incorporates all the essential components of a debris shelter: ridge pole, ribs, lattice, and debris. It's basically big enough to stick your head into.

Brace yourself ninjas. I'm about to bum you out. But if you stick with me, there's rainbow unicorns at the end. I promise.

Brace yourself ninjas. I'm about to bum you out. But if you stick with me, there's rainbow unicorns at the end. I promise. Sui- the waters are rising in the ocean as the glaciers melt, and the rains fall with unseasonable force and frequency.

Sui- the waters are rising in the ocean as the glaciers melt, and the rains fall with unseasonable force and frequency. I've been closely following the climate science for decades, since my work in the wildlife conservation field began over thirty years ago. I worked with critically endangered birds in Hawaii for many years. Hawaii was and unfortunately still is considered "the endangered species capital of the United States." We are in the midst of what is now considered the

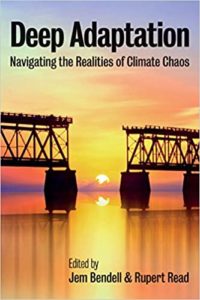

I've been closely following the climate science for decades, since my work in the wildlife conservation field began over thirty years ago. I worked with critically endangered birds in Hawaii for many years. Hawaii was and unfortunately still is considered "the endangered species capital of the United States." We are in the midst of what is now considered the  More recently, there is a new lexicon that has entered the climate change discussion from scientists, policy makers, and the public at large. These discussions include terms such as "tipping point," "the end of growth," "overreach," "collapsology," and even "the extinction of the human species." Many believe we have already passed the tipping point at which we can no longer hold back the devastation and disruption with increasing climate change. This discussion is supported by the fact that increasing average global temperature is no longer a linear progression with CO2 in the atmosphere. In other words, even if we could reverse, or remove the additional CO2 that began increasing with the industrial revolution, the climate would still continue to warm. This non-linear increase is due to things such as reduced solar reflection by snow in the polar regions, increased methane from melting permafrost in the arctic, subsurface oceanic methane release, and changes in the oceanic conveyor belt, to mention a few. There is a very real possibility that we have set things in motion that cannot be stopped at this point.

More recently, there is a new lexicon that has entered the climate change discussion from scientists, policy makers, and the public at large. These discussions include terms such as "tipping point," "the end of growth," "overreach," "collapsology," and even "the extinction of the human species." Many believe we have already passed the tipping point at which we can no longer hold back the devastation and disruption with increasing climate change. This discussion is supported by the fact that increasing average global temperature is no longer a linear progression with CO2 in the atmosphere. In other words, even if we could reverse, or remove the additional CO2 that began increasing with the industrial revolution, the climate would still continue to warm. This non-linear increase is due to things such as reduced solar reflection by snow in the polar regions, increased methane from melting permafrost in the arctic, subsurface oceanic methane release, and changes in the oceanic conveyor belt, to mention a few. There is a very real possibility that we have set things in motion that cannot be stopped at this point. We are also on course for the end of growth, meaning when the growth of civilization collides with the end of finite resources, in other words the "collapse of civilization." This is predicted to occur

We are also on course for the end of growth, meaning when the growth of civilization collides with the end of finite resources, in other words the "collapse of civilization." This is predicted to occur  A 2018 article

A 2018 article  How prepared are we currently for an economic and ecological societal collapse? More than 95% of the food coming into the major cities in our country arrives by long-distance trucking. If this ceased, it is estimated that New York would have a four day supply of food. Los Angeles would have three days of food. In 1880, 50% of Americans were farmers. Today, that number is less than 2%. In 1945, Americans grew 40% of their food in backyard gardens. That number is now less than 0.1%. This is homeland insecurity. I wonder how many Americans today can identify a single wild edible plant? How many know the ubiquitous edible "weeds" in their yards, that they kill with glyphosate herbicides at the cost to their own fertility and health? As I look out my kitchen window during the winter, I ask myself— how can I expand and grow more? What new wild edibles can I learn and find in the nearby forests?

How prepared are we currently for an economic and ecological societal collapse? More than 95% of the food coming into the major cities in our country arrives by long-distance trucking. If this ceased, it is estimated that New York would have a four day supply of food. Los Angeles would have three days of food. In 1880, 50% of Americans were farmers. Today, that number is less than 2%. In 1945, Americans grew 40% of their food in backyard gardens. That number is now less than 0.1%. This is homeland insecurity. I wonder how many Americans today can identify a single wild edible plant? How many know the ubiquitous edible "weeds" in their yards, that they kill with glyphosate herbicides at the cost to their own fertility and health? As I look out my kitchen window during the winter, I ask myself— how can I expand and grow more? What new wild edibles can I learn and find in the nearby forests? These realizations, however, have given me an awakened perspective on the value and role of the art of the ninja when faced with the possibility of collapse. If you examine historical examples of societal collapse, wars or social unrest typically precede or follow the downfall of civilizations. While actually having to defend yourself or others when faced with unrest might be a real matter worthy of discussion, there is a deeper value that I find in the art. The essence of perseverance, or the meaning of "nin," is at the heart of what motivates me daily when I wake. What am I going to do today, to take a necessary step towards adapting to the unknown that lies on the horizon? I have been teaching survival skills for years. Beyond shelter, water, fire, and food, we teach that attitude is the most important survival skill. If you give up, and admit defeat in the face of doom, then you most likely will fail. Remembering to embody the spirit of "nin" is thus essential to survival.

These realizations, however, have given me an awakened perspective on the value and role of the art of the ninja when faced with the possibility of collapse. If you examine historical examples of societal collapse, wars or social unrest typically precede or follow the downfall of civilizations. While actually having to defend yourself or others when faced with unrest might be a real matter worthy of discussion, there is a deeper value that I find in the art. The essence of perseverance, or the meaning of "nin," is at the heart of what motivates me daily when I wake. What am I going to do today, to take a necessary step towards adapting to the unknown that lies on the horizon? I have been teaching survival skills for years. Beyond shelter, water, fire, and food, we teach that attitude is the most important survival skill. If you give up, and admit defeat in the face of doom, then you most likely will fail. Remembering to embody the spirit of "nin" is thus essential to survival. I posed this question to Dai Shihan Mark Roemke regarding this topic: How does the art of the ninja relate to an uncertain future of disruption on our planet? Here is his response.

I posed this question to Dai Shihan Mark Roemke regarding this topic: How does the art of the ninja relate to an uncertain future of disruption on our planet? Here is his response. Beyond my garden, I think about my own kids and the youth I have encountered with the programs I teach. I realize that to simply hope that our governments and corporations can figure out a solution to climate change while continuing "business as usual" is not only foolish, but does an extreme disservice to the youth of today and the future generations. If I make it to 2045, I'll be firmly in my elder years. My kids, grandkids, or great grandkids (if there are still enough viable sperm and eggs by then) will be the ones facing the brunt of this trajectory. There's a song that I love that has the words that speak to this:

Beyond my garden, I think about my own kids and the youth I have encountered with the programs I teach. I realize that to simply hope that our governments and corporations can figure out a solution to climate change while continuing "business as usual" is not only foolish, but does an extreme disservice to the youth of today and the future generations. If I make it to 2045, I'll be firmly in my elder years. My kids, grandkids, or great grandkids (if there are still enough viable sperm and eggs by then) will be the ones facing the brunt of this trajectory. There's a song that I love that has the words that speak to this: I also have a new perspective on the large volume of skills that we have put together for youth with our Ninjas in Nature program. I used to view them primarily as a means to help someone connect deeply to nature, while building powerful self sufficiency, awareness, and self confidence through the martial arts skills. Connect someone deeply to nature, and they will want to save it was once the standard mantra. The end result was a truly happy and whole being, with a desire to preserve nature, and still is. Unfortunately, the pragmatist and former Boys Scout in me remembers the old motto: "be prepared." How to prepare for an uncertain future, with no template from history to go by, is at the core of this challenge for me.

I also have a new perspective on the large volume of skills that we have put together for youth with our Ninjas in Nature program. I used to view them primarily as a means to help someone connect deeply to nature, while building powerful self sufficiency, awareness, and self confidence through the martial arts skills. Connect someone deeply to nature, and they will want to save it was once the standard mantra. The end result was a truly happy and whole being, with a desire to preserve nature, and still is. Unfortunately, the pragmatist and former Boys Scout in me remembers the old motto: "be prepared." How to prepare for an uncertain future, with no template from history to go by, is at the core of this challenge for me. But now I see these skills as essential tools for adapting to the unknown change and disruptions to be faced by the inhabitants of our planet. It's not just the confidence of knowing how to find and process acorns as a vital protein source should the shipping trucks cease to show up, or how to make a fire by friction if the electricity goes down. It's about how to tap into the spirit of perseverance.

But now I see these skills as essential tools for adapting to the unknown change and disruptions to be faced by the inhabitants of our planet. It's not just the confidence of knowing how to find and process acorns as a vital protein source should the shipping trucks cease to show up, or how to make a fire by friction if the electricity goes down. It's about how to tap into the spirit of perseverance. Over 98% of all life that has ever lived on this planet has gone extinct. Think about that. The deck was stacked against us as a species long before we ever appeared on this planet. There have been five major extinction events in the history of planet Earth, and we likely are driving the current extinction bus blindly towards the precipice of the sixth. Still, after every major extinction event, something more beautiful evolved in the aftermath. Dinosaurs and ferns were pretty cool, but the mammals and flowering plants that followed were much more beautiful. I know. I'm a biased mammal. Still, I think the photographers and landscape artists are on my side. While this may sound like a nihilistic doomsday perspective, I find solace in stepping back to look at the wide angle vision, long view of our human time on Earth, and our collective connection to the mystery that holds this tapestry together. There is a beauty to this mystery that we are part of. One definition that I heard recently for "love" is a state of consciousness that is an awareness of beauty. I love the mystery.

Over 98% of all life that has ever lived on this planet has gone extinct. Think about that. The deck was stacked against us as a species long before we ever appeared on this planet. There have been five major extinction events in the history of planet Earth, and we likely are driving the current extinction bus blindly towards the precipice of the sixth. Still, after every major extinction event, something more beautiful evolved in the aftermath. Dinosaurs and ferns were pretty cool, but the mammals and flowering plants that followed were much more beautiful. I know. I'm a biased mammal. Still, I think the photographers and landscape artists are on my side. While this may sound like a nihilistic doomsday perspective, I find solace in stepping back to look at the wide angle vision, long view of our human time on Earth, and our collective connection to the mystery that holds this tapestry together. There is a beauty to this mystery that we are part of. One definition that I heard recently for "love" is a state of consciousness that is an awareness of beauty. I love the mystery.

But before I proceed further, first...The Dunker’s Disclaimer

But before I proceed further, first...The Dunker’s Disclaimer 70's Fahrenheit— In early June last year, my friend Duncan called me on the phone. "Ken, I'd like to work on my crawl stroke. Since you used to coach swimming, could you give me some pointers?" Duncan showed up the next morning, and we started swimming across the pond. I gave him some pointers. The water was a comfortable temperature, in the mid-seventies. We started swimming three times a week at 7 am. Dawn patrol fishermen dotted the shore, and occasional morning swimmers roamed the periphery. After two and a half years living by the pond, I hadn't "trained" by doing long distance swimming in these waters. I usually ventured down daily to romp in the pond with family and friends. For some reason I had been in a rut. I believed the indoor pool was for "training" and outdoors was for fun and play. That was about to change.

70's Fahrenheit— In early June last year, my friend Duncan called me on the phone. "Ken, I'd like to work on my crawl stroke. Since you used to coach swimming, could you give me some pointers?" Duncan showed up the next morning, and we started swimming across the pond. I gave him some pointers. The water was a comfortable temperature, in the mid-seventies. We started swimming three times a week at 7 am. Dawn patrol fishermen dotted the shore, and occasional morning swimmers roamed the periphery. After two and a half years living by the pond, I hadn't "trained" by doing long distance swimming in these waters. I usually ventured down daily to romp in the pond with family and friends. For some reason I had been in a rut. I believed the indoor pool was for "training" and outdoors was for fun and play. That was about to change. 60's— I remember thinking at the pond one morning..."Where did all the swimmers go?" Getting in the water in the morning was starting to feel a bit jolting to my body. When I surfed in California, the ocean water was usually between 55-60 degrees Fahrenheit year round. During the early New England fall, the kids and I had continued surfing in New Hampshire, Boston, and Rhode Island. We had been tracking the local ocean temperature at those locations. The pond temperature felt like it was in the same range. Being curious as to the daily pond temperature, I went to the local hardware store and bought a cheap thermometer. It confirmed that the temperature was in the 60’s. The morning swims felt so refreshing. The hot cup of coffee upon returning home after swims tasted better as I hugged it to my chest for warmth.

60's— I remember thinking at the pond one morning..."Where did all the swimmers go?" Getting in the water in the morning was starting to feel a bit jolting to my body. When I surfed in California, the ocean water was usually between 55-60 degrees Fahrenheit year round. During the early New England fall, the kids and I had continued surfing in New Hampshire, Boston, and Rhode Island. We had been tracking the local ocean temperature at those locations. The pond temperature felt like it was in the same range. Being curious as to the daily pond temperature, I went to the local hardware store and bought a cheap thermometer. It confirmed that the temperature was in the 60’s. The morning swims felt so refreshing. The hot cup of coffee upon returning home after swims tasted better as I hugged it to my chest for warmth. 40's— I kept swimming several times a week in my wetsuit. And then I saw the documentary My Octopus Teacher. In the movie, Craig Foster mentioned that he swam everyday for a year in the South African coastal waters. He said the water was around 5 degrees Celsius year round. I was a big fan of his work and had seen all of his previous documentaries. I pulled up the conversion table. 5 Celsius = 41 Fahrenheit. Craig swam in the movie with only a mask, snorkel, fins, a neoprene hoodie, and shorts. The previous winter I had taken a Wim Hof cold training course and had spent 15 minutes up to my neck in the water on the edge of the pond on a sunny January morning. My January dunk the previous winter was a glimpse into this cold water experience.

40's— I kept swimming several times a week in my wetsuit. And then I saw the documentary My Octopus Teacher. In the movie, Craig Foster mentioned that he swam everyday for a year in the South African coastal waters. He said the water was around 5 degrees Celsius year round. I was a big fan of his work and had seen all of his previous documentaries. I pulled up the conversion table. 5 Celsius = 41 Fahrenheit. Craig swam in the movie with only a mask, snorkel, fins, a neoprene hoodie, and shorts. The previous winter I had taken a Wim Hof cold training course and had spent 15 minutes up to my neck in the water on the edge of the pond on a sunny January morning. My January dunk the previous winter was a glimpse into this cold water experience. The first day it snowed while I was swimming in the pond, Phoebe joined me, paddling the kayak. She wore her favorite rainbow colored snow jacket. The water was warmer than the air, so it actually felt more comfortable to be in the water than standing on shore in the snow. Some winter days though, when the wind blew, and the snow was on the ground, it was really hard to get out of the water (or into the water). One windy winter day my fingers were so cold that I couldn't get my socks on when I emerged. Attempting to insert a wet foot into a fuzzy snow boot resulted in a wardrobe malfunction, and I had to hobble home trying to push my skateboard while wearing floppy boots. It didn't work well.

The first day it snowed while I was swimming in the pond, Phoebe joined me, paddling the kayak. She wore her favorite rainbow colored snow jacket. The water was warmer than the air, so it actually felt more comfortable to be in the water than standing on shore in the snow. Some winter days though, when the wind blew, and the snow was on the ground, it was really hard to get out of the water (or into the water). One windy winter day my fingers were so cold that I couldn't get my socks on when I emerged. Attempting to insert a wet foot into a fuzzy snow boot resulted in a wardrobe malfunction, and I had to hobble home trying to push my skateboard while wearing floppy boots. It didn't work well. Break-Up— As spring approached, the ice began to thaw around the edges and I resumed short dunks and then longer forays. One day as the ice retreated, I donned my wetsuit, hoodie, and gloves and called on my kayak copilot. Being someone who studies "survival" skills, I wanted to have a gauge for how thin ice needed to be to fall through, and what it would feel like to break through thin ice. With Phoebe as my backup, I swam to the edge of the remaining ice sheet and scrambled onto the ice. I jumped up and down until it cracked and I fell through. I did this repeatedly and practiced scrambling out onto thin ice after falling through. I appreciated my wetsuit and my copilot. I learned a lot that day about ice dynamics and how to practice pulling myself out should I ever need the skill. I had so much fun that a few days later I tried it again, but the warming conditions had changed so rapidly that I could no longer scramble onto the ice. Instead, it broke under my arms as I swam. I’d have to wait until next winter to try again.

Break-Up— As spring approached, the ice began to thaw around the edges and I resumed short dunks and then longer forays. One day as the ice retreated, I donned my wetsuit, hoodie, and gloves and called on my kayak copilot. Being someone who studies "survival" skills, I wanted to have a gauge for how thin ice needed to be to fall through, and what it would feel like to break through thin ice. With Phoebe as my backup, I swam to the edge of the remaining ice sheet and scrambled onto the ice. I jumped up and down until it cracked and I fell through. I did this repeatedly and practiced scrambling out onto thin ice after falling through. I appreciated my wetsuit and my copilot. I learned a lot that day about ice dynamics and how to practice pulling myself out should I ever need the skill. I had so much fun that a few days later I tried it again, but the warming conditions had changed so rapidly that I could no longer scramble onto the ice. Instead, it broke under my arms as I swam. I’d have to wait until next winter to try again. "After drop", also known as peripheral vasoconstriction, is what happens after you leave cold water. When your body is exposed to cold, it cleverly closes down the circulation in your limbs in order to keep the core and its vital organs warm. When you get out of the water and put warm clothes on, the body reverses the process. The warm circulation returns to the limbs, but this time the cold blood of the limbs returns to the core body and your core temperature will actually drop. So you start shivering. I'd make my coffee with shivering hands and then sit on a couch wrapped in a wool blanket until the shivering subsided while I read a book.

"After drop", also known as peripheral vasoconstriction, is what happens after you leave cold water. When your body is exposed to cold, it cleverly closes down the circulation in your limbs in order to keep the core and its vital organs warm. When you get out of the water and put warm clothes on, the body reverses the process. The warm circulation returns to the limbs, but this time the cold blood of the limbs returns to the core body and your core temperature will actually drop. So you start shivering. I'd make my coffee with shivering hands and then sit on a couch wrapped in a wool blanket until the shivering subsided while I read a book. It's really hard to describe the sensation of the deep cold swims. The moment I plunged into the cold water, my lungs reflexively gasped, but then, after the first initial strokes, I was just there. Sometimes it was a detached feeling, as if I were an observer watching my arms move through the air and water. Other times I was lost in the experience, as I gazed at the patterns of rocks, stumps, leaves, and fish below me. My favorite moments happened at the end of the swims, when I rolled over, grabbed my buoy and just floated— I lost the boundary between my form and the water, watched the clouds drift, felt my heartbeat in my chest, and was glad to be alive for another day.

It's really hard to describe the sensation of the deep cold swims. The moment I plunged into the cold water, my lungs reflexively gasped, but then, after the first initial strokes, I was just there. Sometimes it was a detached feeling, as if I were an observer watching my arms move through the air and water. Other times I was lost in the experience, as I gazed at the patterns of rocks, stumps, leaves, and fish below me. My favorite moments happened at the end of the swims, when I rolled over, grabbed my buoy and just floated— I lost the boundary between my form and the water, watched the clouds drift, felt my heartbeat in my chest, and was glad to be alive for another day.

I once asked the Grandmaster of ninjutsu, Hatsumi Sensei, "When do we learn the survival techniques like building survival shelters, making fire, fishing line and cordage, trapping animals, hunting and other survival skills?"

I once asked the Grandmaster of ninjutsu, Hatsumi Sensei, "When do we learn the survival techniques like building survival shelters, making fire, fishing line and cordage, trapping animals, hunting and other survival skills?"

calabash bowls for eating. What we didn’t bring was food.

calabash bowls for eating. What we didn’t bring was food.

There’s much more to this story, which I will share in future posts. I hope this story helps inspire people to go into nature and push yourself occasionally. It’s good to sometimes be uncomfortable in situations that you might not think you could ever endure.

There’s much more to this story, which I will share in future posts. I hope this story helps inspire people to go into nature and push yourself occasionally. It’s good to sometimes be uncomfortable in situations that you might not think you could ever endure.

Over twenty years ago I met a young instructor at the world-renowned Tracker School, run by Tom Brown Jr. He was teaching bow and arrow making, among other skills. I was blown away by his attention to detail and craftsmanship. In a subsequent course, the "scout class," all students, myself included, made "scout pits" which were hidden, subterranean sleeping shelters that we slept in during the week-long course. This young instructor was also teaching at that class, however, I learned that he had taken the subterranean sleeping shelter to another level. At the time, he was living in an underground hogan shelter that he built, complete with a fire chimney that exited secretly through an old hollow stump on the surface.

Over twenty years ago I met a young instructor at the world-renowned Tracker School, run by Tom Brown Jr. He was teaching bow and arrow making, among other skills. I was blown away by his attention to detail and craftsmanship. In a subsequent course, the "scout class," all students, myself included, made "scout pits" which were hidden, subterranean sleeping shelters that we slept in during the week-long course. This young instructor was also teaching at that class, however, I learned that he had taken the subterranean sleeping shelter to another level. At the time, he was living in an underground hogan shelter that he built, complete with a fire chimney that exited secretly through an old hollow stump on the surface. Tom and I actually live in the same town of Santa Cruz, California. I first heard of Tom through local friends. I met him when we did a podcast interview of him at his house several years ago. We discussed how survival skills and ninjutsu go together. Little did I know that I would be going to one of his island survival courses a few years later. More on that adventure in an upcoming post. That first experience with Tom would lead me to some really fun adventures in nature. I'm really excited that we get to work with Tom. He's an amazing survival skills instructor and is very tuned in to the natural world.

Tom and I actually live in the same town of Santa Cruz, California. I first heard of Tom through local friends. I met him when we did a podcast interview of him at his house several years ago. We discussed how survival skills and ninjutsu go together. Little did I know that I would be going to one of his island survival courses a few years later. More on that adventure in an upcoming post. That first experience with Tom would lead me to some really fun adventures in nature. I'm really excited that we get to work with Tom. He's an amazing survival skills instructor and is very tuned in to the natural world.

Another experience stands out. While staying with a tribe in the Amazon, a hunter named Nanto and I wandered too far into an "undiscovered" tribe's territory in the jungle. They are a very hostile group. Many intruders into their territory have been found dead with a spear in them. One day, we were out blow-gunning birds and came upon Puma tracks on a tree. Nanto mentioned that the shaman had told him that he needed to be wary of Puma as they were a sign that he was in danger. Soon after that, we came across two spears crossed in an 'X' across the trail. Essentially this was our one warning that this one tribe, the Taegeri, were watching and they were telling us that we had gone too far. If we went any further, that would have been the end. Nanto was pretty shaken up when he saw that, which made me literally shake. Luckily we took the warning, turned around, and quickly headed back to his village.

Another experience stands out. While staying with a tribe in the Amazon, a hunter named Nanto and I wandered too far into an "undiscovered" tribe's territory in the jungle. They are a very hostile group. Many intruders into their territory have been found dead with a spear in them. One day, we were out blow-gunning birds and came upon Puma tracks on a tree. Nanto mentioned that the shaman had told him that he needed to be wary of Puma as they were a sign that he was in danger. Soon after that, we came across two spears crossed in an 'X' across the trail. Essentially this was our one warning that this one tribe, the Taegeri, were watching and they were telling us that we had gone too far. If we went any further, that would have been the end. Nanto was pretty shaken up when he saw that, which made me literally shake. Luckily we took the warning, turned around, and quickly headed back to his village. Tom: One of my favorite shelters I have ever lived in was one that was a completely underground hogan. To get into the shelter you would lift a small oak bush to reveal a door, then climb down a ladder into the shelter. One could walk directly over it and not know it was there. I even had a “chimney” going into a hollow tree stump to dissipate the smoke so you wouldn't notice it.

Tom: One of my favorite shelters I have ever lived in was one that was a completely underground hogan. To get into the shelter you would lift a small oak bush to reveal a door, then climb down a ladder into the shelter. One could walk directly over it and not know it was there. I even had a “chimney” going into a hollow tree stump to dissipate the smoke so you wouldn't notice it. Tom: After 25 years since making my first friction fire, I still get a huge kick out of it. When I lived in the woods at age 18 for a year, I wouldn't allow myself to have any fire unless I got it with a hand drill or bow-drill. After consistently getting friction fire for 6 months, one day it just stopped working. I still don’t understand why, but I could not get a friction fire for about 5 days. This was in the middle of December, so you can imagine how difficult it was to not have light or warmth in my shelter, warm food and all the things I was taking for granted. After 5 days, to finally get that back was incredible. I was so grateful then and still feel grateful even today when I get a fire.

Tom: After 25 years since making my first friction fire, I still get a huge kick out of it. When I lived in the woods at age 18 for a year, I wouldn't allow myself to have any fire unless I got it with a hand drill or bow-drill. After consistently getting friction fire for 6 months, one day it just stopped working. I still don’t understand why, but I could not get a friction fire for about 5 days. This was in the middle of December, so you can imagine how difficult it was to not have light or warmth in my shelter, warm food and all the things I was taking for granted. After 5 days, to finally get that back was incredible. I was so grateful then and still feel grateful even today when I get a fire.

Tom: I try to pour myself into every book of that area to learn about plant life. Then I try to see what indigenous people of that area do/did. I think through all the potential problems I could face and try to play it all out in my head beforehand. Of course there are always surprises, and I only find a few of the hundreds of plants I have studied. But, I do plan for how to provide the basics of Shelter, Water, Fire, Food. After that, I just try to get creative based on what I discover in real-time.

Tom: I try to pour myself into every book of that area to learn about plant life. Then I try to see what indigenous people of that area do/did. I think through all the potential problems I could face and try to play it all out in my head beforehand. Of course there are always surprises, and I only find a few of the hundreds of plants I have studied. But, I do plan for how to provide the basics of Shelter, Water, Fire, Food. After that, I just try to get creative based on what I discover in real-time. Tom: I feel really fortunate to have spent a year living off the land when I was 18. That entire year I spent about $300-$400 in total. What this has gifted me is the ability to know that no matter what happens in my life, I can always go back to that forest and do that again. Because of this, I felt free to take chances on pursuing my passions rather than always playing it safe. I always had an answer to the big “what if things fall apart?” question. I think this gives people confidence to live in less fear, even if they never actually use it. Knowing you can survive off the land gives you a confidence that even the wealthiest person does not have.

Tom: I feel really fortunate to have spent a year living off the land when I was 18. That entire year I spent about $300-$400 in total. What this has gifted me is the ability to know that no matter what happens in my life, I can always go back to that forest and do that again. Because of this, I felt free to take chances on pursuing my passions rather than always playing it safe. I always had an answer to the big “what if things fall apart?” question. I think this gives people confidence to live in less fear, even if they never actually use it. Knowing you can survive off the land gives you a confidence that even the wealthiest person does not have. Tom: In one of my classes, there was a Master Chief from the Navy Seals. He was built like a Greek God and probably one of the scariest people I could ever meet. He had been in the Seals for more than 20 years, and I can't imagine the talents he possessed. During one class on tanning deer hides, my co-instructor had everyone make small leather bags of the buckskin. She taught everyone how to sew various stitches and at some point this Navy Seal called me over asking me how to do a ‘whip-stitch’. I told him that for a guy as tough as he was, I found it funny he was asking me how to sew a tiny little leather pouch to go around his neck. Surely this was beneath him at this point. He then looked at me and commented that being a warrior was about collecting as many skills as possible, and the only way he rose to the top of the Seal program was because he never stopped learning, and finding new things to learn.

Tom: In one of my classes, there was a Master Chief from the Navy Seals. He was built like a Greek God and probably one of the scariest people I could ever meet. He had been in the Seals for more than 20 years, and I can't imagine the talents he possessed. During one class on tanning deer hides, my co-instructor had everyone make small leather bags of the buckskin. She taught everyone how to sew various stitches and at some point this Navy Seal called me over asking me how to do a ‘whip-stitch’. I told him that for a guy as tough as he was, I found it funny he was asking me how to sew a tiny little leather pouch to go around his neck. Surely this was beneath him at this point. He then looked at me and commented that being a warrior was about collecting as many skills as possible, and the only way he rose to the top of the Seal program was because he never stopped learning, and finding new things to learn.

Over thirty years ago, one of Jon's first students was a young guy named Dan Gardoqui. Today Dan is one of the preeminent trackers, naturalists, and mentors of nature connection in North America. He co-founded and was Executive Director for the White Pines Program in Maine. He lives in Maine today where he runs

Over thirty years ago, one of Jon's first students was a young guy named Dan Gardoqui. Today Dan is one of the preeminent trackers, naturalists, and mentors of nature connection in North America. He co-founded and was Executive Director for the White Pines Program in Maine. He lives in Maine today where he runs  goal is to get closer to a moose in the fall, I am going to go to a place on the landscape where I am most likely to find them. So I have to understand what moose are eating, what they are thinking, what they are doing biologically that time of year which is their rut. Or after their rut when they are done breeding, I need to know if they are likely to be alone, or in pairs, or in bachelor groups. If they are in their thicker winter fur and it's a warmer day, they are going to be seeking out cooler and moister areas, so I'm going to have to think about microhabitats. I'm going to have to think about the cool pockets on the landscape. Ecological awareness flows with the rhythms of nature and is about understanding the natural history of animals and how habitats are preferential or not to different animals.

goal is to get closer to a moose in the fall, I am going to go to a place on the landscape where I am most likely to find them. So I have to understand what moose are eating, what they are thinking, what they are doing biologically that time of year which is their rut. Or after their rut when they are done breeding, I need to know if they are likely to be alone, or in pairs, or in bachelor groups. If they are in their thicker winter fur and it's a warmer day, they are going to be seeking out cooler and moister areas, so I'm going to have to think about microhabitats. I'm going to have to think about the cool pockets on the landscape. Ecological awareness flows with the rhythms of nature and is about understanding the natural history of animals and how habitats are preferential or not to different animals. Dan: This one is fun. "Helper" is a bit biased. It implies that the animals have the intention of being helpful to humans, and they may actually. I'm not sure we can say they definitely do or definitely don't. Some of the most well known examples are of ravens. There are many stories about these birds and how they sometimes act as guides to help people or other animals find certain things on a landscape, such as carcasses or prey species. If you pay attention to some basics of how ravens communicate, and if you are open to the fact that you are in communication with them, because frankly we all are in communication with the animals in one way or another whether we are conscious of it or not, then they can truly help you with some of your goals. The flip side of this relationship is that the ravens also get a benefit. For instance, if you are a hunter, and the ravens are helping you find your prey, after you successfully get that animal, you may leave parts of that animal behind after you process it. Then, the ravens will benefit from this food. There are other examples of this such as the honey guides in Africa.

Dan: This one is fun. "Helper" is a bit biased. It implies that the animals have the intention of being helpful to humans, and they may actually. I'm not sure we can say they definitely do or definitely don't. Some of the most well known examples are of ravens. There are many stories about these birds and how they sometimes act as guides to help people or other animals find certain things on a landscape, such as carcasses or prey species. If you pay attention to some basics of how ravens communicate, and if you are open to the fact that you are in communication with them, because frankly we all are in communication with the animals in one way or another whether we are conscious of it or not, then they can truly help you with some of your goals. The flip side of this relationship is that the ravens also get a benefit. For instance, if you are a hunter, and the ravens are helping you find your prey, after you successfully get that animal, you may leave parts of that animal behind after you process it. Then, the ravens will benefit from this food. There are other examples of this such as the honey guides in Africa. to humans as well. Knowing our human behaviors and patterns is really helpful and wise when we want to stay safe and alert. But, also start to pay attention to everything else. It can be pigeons, crows, rats, squirrels, little sparrows. Start to give your attention to things that are not human and be open to a fact that they are speaking a language that we can understand. Just start being curious, ask questions, and develop relationships with them. The more you spend time in the same place, quietly listening and observing and being open, chances are those individuals are going to get used to you being there. When you give them your attention and respect, they are probably going to do the same for you. Start by just listening, watching, and giving them space. Say you are walking down a sidewalk, and there's a pigeon in front of you feeding on the sidewalk, just slow down and go around it. If you start to give birds a little more space and respect, it changes the dynamics, and it changes the way you see the world.

to humans as well. Knowing our human behaviors and patterns is really helpful and wise when we want to stay safe and alert. But, also start to pay attention to everything else. It can be pigeons, crows, rats, squirrels, little sparrows. Start to give your attention to things that are not human and be open to a fact that they are speaking a language that we can understand. Just start being curious, ask questions, and develop relationships with them. The more you spend time in the same place, quietly listening and observing and being open, chances are those individuals are going to get used to you being there. When you give them your attention and respect, they are probably going to do the same for you. Start by just listening, watching, and giving them space. Say you are walking down a sidewalk, and there's a pigeon in front of you feeding on the sidewalk, just slow down and go around it. If you start to give birds a little more space and respect, it changes the dynamics, and it changes the way you see the world. Dan: This is what I was just talking about. Doing the quiet sits and giving birds your attention and respect for example. Doing this just helps us get out of our own little bubble of thoughts, emotions, and things that might cause disturbance around us. If you think of yourself as moving through a pond, when the mind is quiet, the ripples you cause and the way you move is much smoother, so there are many less ripples or disturbances. When the mind is busy, we tend to cause quite a wake, ahead and behind us. This tends to push things away from us. Many species are very sensitive to our thoughts and emotions, and where we are in our heads, including our own species. It's easy to tell if your family or friends are in a tough space or not. So it's silly to think that wildlife can't detect this as well. Whatever helps you to get to this calm mental space, be it yoga, breathing exercises, or meditation, it's going to help you be more "invisible" in the forest. But it's not really being invisible to me because that means we are trying to hide from something. To me it's more about having integrity with the vibe of a forest or nature. It's not thinking that our human existence is the most important thing. It's just being open to all the other things that exist around us.

Dan: This is what I was just talking about. Doing the quiet sits and giving birds your attention and respect for example. Doing this just helps us get out of our own little bubble of thoughts, emotions, and things that might cause disturbance around us. If you think of yourself as moving through a pond, when the mind is quiet, the ripples you cause and the way you move is much smoother, so there are many less ripples or disturbances. When the mind is busy, we tend to cause quite a wake, ahead and behind us. This tends to push things away from us. Many species are very sensitive to our thoughts and emotions, and where we are in our heads, including our own species. It's easy to tell if your family or friends are in a tough space or not. So it's silly to think that wildlife can't detect this as well. Whatever helps you to get to this calm mental space, be it yoga, breathing exercises, or meditation, it's going to help you be more "invisible" in the forest. But it's not really being invisible to me because that means we are trying to hide from something. To me it's more about having integrity with the vibe of a forest or nature. It's not thinking that our human existence is the most important thing. It's just being open to all the other things that exist around us. places before you decide the techniques you are going to use to blend in with that place. For instance, the pace that you would move in a busy city street in rush hour in order to blend in better be pretty quick. Whereas the pace you are going to use in a quieter rural wild area will probably be a bit slower. So getting to know the baseline of a place and how to blend in with that baseline and how to be invisible, that's part of the stealth and camouflage. So you really need to know a place. Camouflage is not just about colors and patterns. It's about our energy and speed, our body movements, and where we put our eyes. There's all sorts of little tricks in there.

places before you decide the techniques you are going to use to blend in with that place. For instance, the pace that you would move in a busy city street in rush hour in order to blend in better be pretty quick. Whereas the pace you are going to use in a quieter rural wild area will probably be a bit slower. So getting to know the baseline of a place and how to blend in with that baseline and how to be invisible, that's part of the stealth and camouflage. So you really need to know a place. Camouflage is not just about colors and patterns. It's about our energy and speed, our body movements, and where we put our eyes. There's all sorts of little tricks in there.

a rafting trip down the Grand Canyon. One day of the trip, we went for a five mile hike up into the desert canyon. The temperature was over 110 degrees F. The dry desert landscape showed little sign of fresh water. That changed as we rounded a bend in the trail that put us at the base of a 500 foot high red wall limestone rock face. Hundreds of feet above us an enormous spring roared out of the rock wall face from a cave, landing in a large pool at the bottom of the cliff. It was the only time in my life that I have ever swam and drank the water at the same time. I can still hear the roar of the water fall. The dramatic contrast with the parched landscape surrounding this spring highlighted the value of this amazing resource.

a rafting trip down the Grand Canyon. One day of the trip, we went for a five mile hike up into the desert canyon. The temperature was over 110 degrees F. The dry desert landscape showed little sign of fresh water. That changed as we rounded a bend in the trail that put us at the base of a 500 foot high red wall limestone rock face. Hundreds of feet above us an enormous spring roared out of the rock wall face from a cave, landing in a large pool at the bottom of the cliff. It was the only time in my life that I have ever swam and drank the water at the same time. I can still hear the roar of the water fall. The dramatic contrast with the parched landscape surrounding this spring highlighted the value of this amazing resource.